Boatswain’s mate on the Bounty, James Morrrison (1760–1807) lived on Tahiti for two years from 1789 to 1771, quickly learning the language and gaining an insightful understanding of Tahitian life and culture before the arrival of Protestant missionaries. His ethnography of funeral ritual and mourning ceremonies shows both keen observation and a lively sympathy for the people. The excerpted passages below are from an electronic text version of Morrison’s Account of the Island of Tahiti & the Customs of the Island. It can be found online in the Indigenous histories section of the digital humanities resource, South Seas: Voyaging and Cross Cultural Encouters in the Pacific (1760–1800),and is, in turn, derived from Owen Rutter’s edition of the Journal of James Morrison, Boatswain’s Mate of the Bounty, describing the Mutiny and subsequent Misfortunes of the Mutineers together with an account of the Island of Tahiti (London: Golden Cockerel Press, 1935).

A scholarly edition, edited by Vanessa Smith and Nicholas Thomas, Mutiny and Aftermath: James Morrison’s Account of the Mutiny on the Bounty and the Island of Tahiti, is also available, recently published by the University of Hawaii Press in 2013.

When any person dies the relations flock to the House in numbers making much lamentation and the Weomen cut their heads with sharks teeth; both sexes cut their hair off different parts of their heads, somtimes Cutting all of but a lock over one Ear, somtimes over both & the rest Close cut or shaven. The Weomen often Cut themselves on these occasions till they bring on a fever and I have known a Woman Cut herself for the loss of a Child till a delirium was brought on which ended in the total loss other reason.

For the loss of a relation they Cut a square place bare on the fore part of their head which they keep bare for 6 Moons or longer, according to the love they bear the deceased; but for a favourite Child they wear it so for two or 3 Years and all the hair they Cut off is either thrown into the Sacred Ground or Carried to the Morai.

If any Person dies of a Disorder they are Buried in their own Ground and a Priest always puts a Plantain tree into the Grave with them and some of the relations put them in the Grave, praying them to keep their disorder in the Grave with them and not afflict any person with [it]. When their Soul is Sent on that Business, they also bury or burn evry thing belonging to them, or that has been used by them while in their Sickness, house and furniture to prevent the disorder from spreading or Communicating to others — these are the only people that have any funeral Prayers — thosewho die without disease are either laid on a beir or embalmd. Their Method of embalming is by taking the Bowells out and Stuffing the Body with Cloth and grated Sandal wood, anointing the skin with Cocoa Nut oil scented with the Same wood; the Body is laid on a Beir in a house by itself & Covered with Cloth which the relations present as they Come to the Place, which they all do if they are in the Island. The body is often dressd in the same Manner as it used to do while alive, the Head Ornamented with Flowers, the house is fenced in and hung round with Cloth finely scented and the beir is ornamented with Garlands of Palm Nuts which having an agreeable Smell keep off any foul one — The Tears Shed on these Occasions are saved on peices of Cloth together with the Blood from their heads, and thrown within the rail of the Sacred house, all which they suppose gives satisfaction to the departed soul, who [is] hovering about the Body while it remains without Moldering — Others are hung up on a Beir under a thatchd Covering Covered and dressd with Cloth; they are also ornamented with Palm Nuts, Cocoa Nut leaves platted in a Curious Manner and raild in with reeds which the Man that is appointed to take Care of the Body keeps in repair, and he is obliged to have a Man to feed him as he must not toutch any sort of food for one Month, after he has toutchd a dead body or any of the things which belong to it — they also offer Provisions &c. near the Corps not for it but the Deity who presides over it.

The body is Calld Toopapow, the Beir Fwhatta and the House wherein it is Containd Farre Toopapow — those who are embalmed are Calld Toopapow Meere — They are kept each on their own land and Not Carryd to the Moral where none are interrd, but those Killd in War, or for Sacrafice or the Children of Chiefs who have been Strangled at their birth.

When Chiefs or People of rank die their bodys are Embalmed and they are Carried round the Island to evry part where they have any Posessions, in each of which the Tyehaa or Weeping Ceremony is renewd; and after a Journey of 6 or 8 Months returns to their own estate where they are kept till the Body decays when the bones are interd. Some who have a great Veneration for the deceased wrap up the Scull and Hang it up in their house in token of their love and in this Manner is the Sculls of several kept — these bodys, while they are whole, are liable to be taken in War and the Man who takes one of them gets the Name and honors as if He had killd a Warrior, and should the body of a Chief be Carried off in this Manner before an other was Named the District would fall to the Conqueror as if he had killd him; for this reason they are always removed, having each a Steady Man to Carry them away into the Mountains if they should be in War, in this Manner Captain Cooks picture is also removed lest it should be taken — While the Body remains they keep the Beir well supplyd with Cloth & new is always substituted in lieu of that which is decayd and the Cloth is in general good and neatly painted.

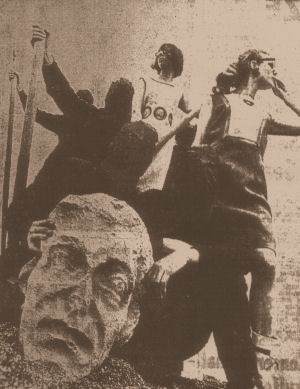

Besides the Weeping and Cutting their Heads they have another Mourning Ceremony wherin they wear the Pari or Mourning Dress described by Captain Cook. — This is Mostly worn by two or three of the Nearest Male relations each of which are Armd with a Weapon Calld Paaeho, edged with a row of sharks teeth for three feet or four of its length, the Upper part forming a blade like that of a Gardners knife. They are attended by forty or fifty Young Men & Weomen who disguise themselves by blacking their bodys and faces with Charcoal, and spotting them with pipe Clay; these seldom wear any other Cloths but a Marro and each is armd with a Spear or Club and parade about the district like Madmen and will beat Cut or even kill any person who offers to stand in their Way — therefore when any one sees them Coming they fly to the Morai, it being the only place where they can be safe, or Get refuge from the rage of the Mourners who persue all that they see. The Morai alone they must [not] enter, and while this Ceremony lasts, which is somtimes 3 weeks or a month, they pay no respect to persons nor are the Chiefs safe from their fury unless they take sanctuary in the Morai; the Weomen and Children are forced to quit the place as they Cannot take refuge in the Morai.

Should any person be stubborn or foolish enough to stop one of the Mourners or Not get out of their way and they should be killd no law can be obtaind nor any blamed but himself, as the Mourners are look’d on as lunaticks, driven Mad through Grief for the Death of their relations therefore none attempt to obstruct them but fly at their approach. This Ceremony is also Calld Tyehaa or Mourning, the Performers are Calld Naynevva, Madmen Hevva tyehaa — Mourning Spirits, Gosts, or Spectres.

These are the whole of their Mourning rites and are of longer or shorter duration according to the circumstances of the Family who have lost their relation. They are more particularly observed for Children then Grown persons.